I’ve mentioned before that while most of my blog readers are extremely talented and impressive artists and writers of all sorts in 135 countries, I don’t usually write about technique. That information can be gotten in a thousand places, and usually what’s said you’ve heard 200 times before. No, the turf I’ve staked out for myself concerns what I call The Inner Skills of Creative People. For there, I think, inside you, in your spirit, will be found the magical difference between run of the mill, adequate creators and great ones. Technique is important but will take you only so far. There’s more to being a creator. There is just something about great painters, writers, dancers, and actors that makes them great, and it comes from within.

So I write freely and happily about such creators’ necessities as courage, persistence, tenacity, will power, commitment, empowerment, sense of purpose, and discipline. And resilience, enthusiasm, guts, self-motivation, boldness, doggedness, adaptability, endurance, and other spiritual dimensions of you, the creator.

And today I’ll write about the creator’s Inner Skill of optimism.

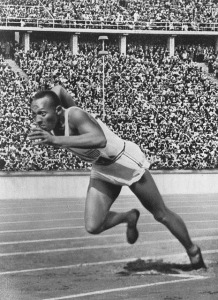

What separates winners from losers, Olympic athletes from other world class competitors? According to a group of researchers who studied America’s top wrestlers, the difference is not in physical ability, and it’s not in training methods–they’re pretty standard. Wrestlers eliminated in Olympic trials tended to be self-doubting, confused, and pessimistic before the match. The winners were optimistic, positive, and relaxed. Those who made the team were also more poised and in control of their reactions than the losers, who were more likely to become emotionally upset. The researchers were able to predict 92% of the winners by using profiles of the wrestlers alone–without seeing a single wrestling match!

It’s not only in athletic performance that optimists fare better than pessimists, but in school and work performance too. In one experiment, students’ success on tests was more related to their optimism than to their intelligence. A positive, optimistic frame of mind increases power and effectiveness. A pessimistic frame of mind depletes them.

One major job of writers and artists is to sell their work—to magazines and publishers, and galleries, show sponsors, and clients. It stands to reason that the more optimistic writer and artist will have more selling success than their  pessimistic counterparts because optimists make better sales people than pessimists. A study was done of two groups of people selling over the phone. One group was comprised of trained and experienced sales people who were pessimistic. The others were women who didn’t have a single day of experience or training in sales at all, but scored high on a test for optimism. The untrained and inexperienced women optimists easily out-performed the trained and experienced pessimists. So if you’re not a natural optimist, you may wish to see the strategies below.

pessimistic counterparts because optimists make better sales people than pessimists. A study was done of two groups of people selling over the phone. One group was comprised of trained and experienced sales people who were pessimistic. The others were women who didn’t have a single day of experience or training in sales at all, but scored high on a test for optimism. The untrained and inexperienced women optimists easily out-performed the trained and experienced pessimists. So if you’re not a natural optimist, you may wish to see the strategies below.

Anyone who’s trying to be creative should aim for an optimistic mood. Pessimism decreases creative productivity. But a mood of optimism improves problem-finding and problem-solving abilities, and if there are two abilities every creator needs it is to be able to find the main problems to solve and to be able to solve them. Creators in an optimistic mood feel safe, which fosters bolder, more relaxed and creative approaches. Optimists are more willing to take risks.

Optimism entails:

- Feeling free and easy as you write, paint, dance, or act.

- Being collected, composed, and calm; not fretting and worrying or being grumpy, resentful, or irritable.

- Putting unsolvable problems aside, forgiving yourself for past mistakes and letting them go.

- Being decisive and taking actions that will benefit you.

- Thinking hopefully.

- Being endlessly curious about life and confident that you can handle whatever it brings.

- Maintaining hope and faith in the rightness of things and the future, and that things will work out for the best; trusting your luck.

- Ridding yourself of bad habits.

- Having confidence and feeling in control of things and master of your destiny.

- Being open, trusting, genuine, sincere, kindly, and generous with others.

- Being brave and totally focused and clear-minded in action.

- Experiencing moments of bliss knowing that at that moment you and your life are at their best.

- Never letting setbacks penetrate your spirit; expecting to succeed and not to fail.

- Holding no illusions, but knowing exactly where you are in life, where you want to be, and how you’re going to get there.

- Having implicit and unshakable confidence in your goals and not budging a single inch from them, being willing to work hard for them, knowing that fear is your most powerful enemy and that there’s nothing to fear and no reason to hold anything back.

This is the route to optimism and personal power.

Pessimistic writers and artists believe they’re not in control, that creative tasks are too much for them. If you believe you’re not in control, you set lower goals and have a weak commitment to them. But the more strongly you believe that you are in control the higher the goals you set, the stronger your determination to achieve them, and the longer you persevere, even in the face of adversity. Optimistic writers and artists take adversity as a challenge and aren’t discouraged. Trouble ignites them, it fires them up; they’re confident, and they come to life. Even as a young poet Anne Sexton sent out a poem as soon as it was rejected. Sometimes she sent out the same poem fifteen times.

Optimists are able to persist just as strongly in the face of difficulties as when everything is rosy because they have absolute confidence in themselves and hold a favorable view of their future. Persisting rather than giving up, they’re more likely to succeed. Succeeding increases their self-confidence and optimism even more, and they apply themselves again. This cycle is true of people doing any kind of work, from workers on an assembly line to their supervisors, from students to their teachers, from children to their parents, from one writer or artist to another: wherever you find optimists and pessimists.

Optimists are able to persist just as strongly in the face of difficulties as when everything is rosy because they have absolute confidence in themselves and hold a favorable view of their future. Persisting rather than giving up, they’re more likely to succeed. Succeeding increases their self-confidence and optimism even more, and they apply themselves again. This cycle is true of people doing any kind of work, from workers on an assembly line to their supervisors, from students to their teachers, from children to their parents, from one writer or artist to another: wherever you find optimists and pessimists.

Optimism does not take the place of talent, focus, hard work, and the development of skills. But if there are two equally talented and hardworking artists or writers–an optimist and a pessimist–the optimist will go further and have more success. And pessimism can destroy creative talent.

Seven Strategies for Maintaining Your Optimism

- Think optimistic and hopeful thoughts–not just once in a while, but all the time, whatever the circumstances. When you find yourself thinking unpleasantly, pessimistically, change and think optimistic thoughts. The only way to drive out an undesirable thought is by substituting a powerful desirable thought. By thinking differently, you can replace writers’ and artists’ self-doubt and discouragement with self-confidence, fear with courage, boredom with interest, and pessimism with optimism. Don’t dwell on the negative, but jump over to the positive every time. Be like a fish in a stream and swish your tail and quickly change directions. Think thoughts that make you feel free and easy, composed and confident, free of worry, and brave. Just kick every other kind of thought out of your mind.

- Be addicted to goals and action. The path to living optimistically lies in action. Optimistic action immediately invigorates you.

- Always maintain high hopes no matter what. The question isn’t whether you’ll experience defeat, but how you’ll handle it when you do. Everyone without a single exception takes it on the chin sometime. When you’re beaten–by an event, a situation, a circumstance, a person–gather yourself up, be resolved, and come back again. Never let misfortune penetrate your depths. Setbacks can’t defeat an optimistic and determined person. That’s not possible. The optimism of a creative person needs to be indestructible.

- Don’t dwell on past failures. Why punish yourself with what didn’t work out? When you’re knocked down, get up right away. Get back on your feet. Regain your bearings. The next moment offers a reprieve, a new beginning. Seize it.

- Continually look to past successes. List them on a sheet of paper and you’ll see how long a list can be. Look at them when you doubt yourself and your optimism will return.

- Spend time with optimists as much as possible. Birds of a feather flock together, so choose your birds very carefully.

- Learn to play. The joke goes that a horse sits down at a bar and the bartender says, “Why the long face?” You run into long-faced people at work, the check-out stand, the post office, writers’ groups and artists’ groups–everywhere–all the time. But people with a sense of humor are happier, healthier, and more optimistic.

You know very well that if your thoughts are pessimistic–if you’re “off”–your commitment to action is not 100% and your spirit and energy are weak. You don’t feel like working; you take the day off. But when you’re optimistic and know what you want and are confident you can get it, you’re able to devote yourself to it with a powerful singleness of purpose. When you’re like that there is almost no way of stopping you from any success you dream of.

You know very well that if your thoughts are pessimistic–if you’re “off”–your commitment to action is not 100% and your spirit and energy are weak. You don’t feel like working; you take the day off. But when you’re optimistic and know what you want and are confident you can get it, you’re able to devote yourself to it with a powerful singleness of purpose. When you’re like that there is almost no way of stopping you from any success you dream of.

© 2016 David J. Rogers

For my interview from the international teleconference with Ben Dean about Fighting to Win, click on the following link:

Order Fighting to Win: Samurai Techniques for Your Work and Life eBook by David J. Rogers

or

Order Waging Business Warfare: Lessons From the Military Masters in Achieving Competitive Superiority

or

Mastery models in your life should discuss ways in which their confidence in themselves helped them to achieve their desired goals, and their errors and failures they had before eventually performing at a mastery level, and the work they put in to reach success. Ideally, the mastery model will be a warm, enthusiastic, and encouraging person who is trying to help someone else learn new behaviors after possible years doing things in a different, less productive way.

Mastery models in your life should discuss ways in which their confidence in themselves helped them to achieve their desired goals, and their errors and failures they had before eventually performing at a mastery level, and the work they put in to reach success. Ideally, the mastery model will be a warm, enthusiastic, and encouraging person who is trying to help someone else learn new behaviors after possible years doing things in a different, less productive way.